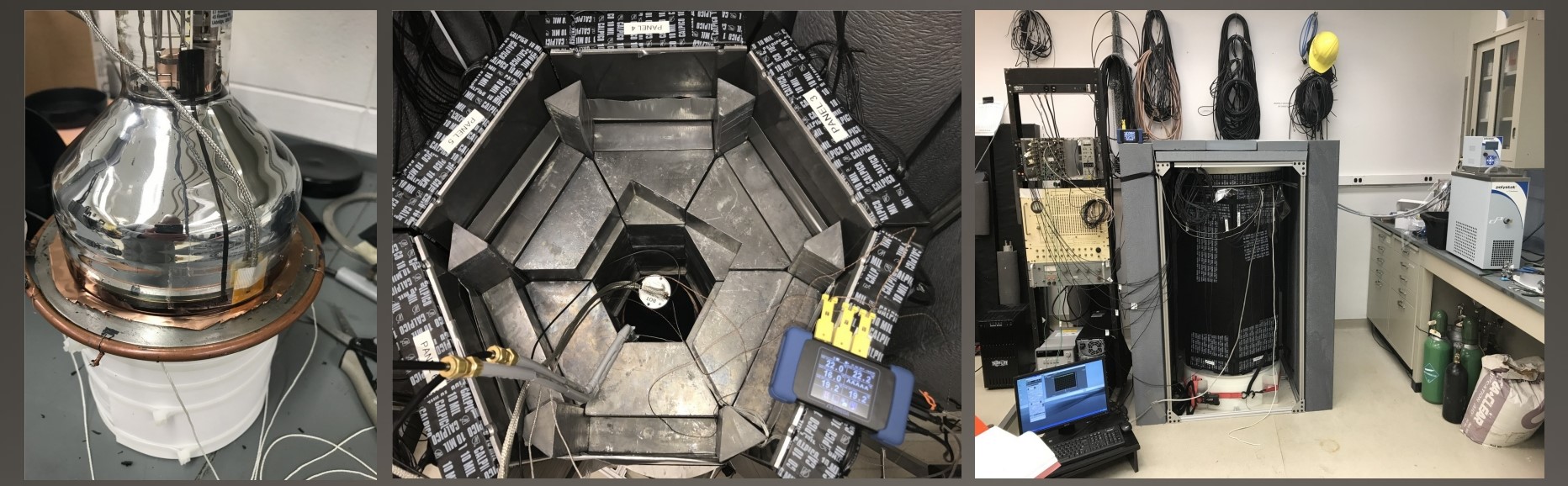

Above are pictures of Carlos Blanco's research teams' first experimental setup of a dark matter detector made using an organic liquid scintillator. This is an example of what these detector setups often look like. This was taken in Professor Juan Collar's lab at the University of Chicago in 2019. CREDIT: Carlos Blanco

ICDS co-hire seeks out signatures of dark matter

Posted on June 2, 2025UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — Looking for signatures of dark matter requires materials sensitive enough to detect the feeblest interactions. Carlos Blanco, Penn State Institute for Computational and Data Sciences (ICDS) co-hire and assistant professor of physics in the Eberly College of Science, is focused on working with experts within Penn State and beyond to do just that.

“We have this modern model of how the universe works — Lambda-CDM — which is a mathematical model that predicts how the universe evolves over time,” Blanco said. “We have incredibly precise data that shows that this model is the correct way to think about the universe. This model does not work without the existence of dark matter. In some ways, it is the defining evidence that dark matter plays a huge role in how the universe evolves overall. Dark matter needs to be there for the universe to exist as it does. Dark matter comprises 80% of all the matter of the universe and we know almost nothing about it.”

According to Blanco, researchers do not know how heavy dark matter particles are, how they interact, or how they are generated in the early universe.

“One of the key ways to learn more information is to attempt to detect any of its interactions with ordinary matter,” he said.

Blanco plans to use ICDS Roar resources to perform particle propagation calculations —which stimulate how high-energy particles propagate throughout the universe and their contents — as well as materials modeling and machine learning models to predict new materials needed to look for direct signals of dark matter.

Blanco looks for dark matter by proposing novel direct detection techniques which are carried out in a laboratory. He also searches for indirect signatures in astrophysical objects from nearby planets to far away galaxies.

“In the lab, we are looking for particles of dark matter traveling very fast — 300 kilometers per second — and hitting our detectors causing a flash of light or having a charge displaced,” Blanco said. “These signatures, however, are very feeble and rare. The detectors we construct must be extremely sensitive and clean and must be without background noise. We are essentially exposing the detectors to nothing, or a completely dark room, to see if there are excess flashes of light or charges.”

In his research, he is looking to find new materials that could be sensitive to dark matter interactions. He uses generative AI models to predict material properties but also what materials would have properties that would be ideal for detecting dark matter.

“I want to do more experiments and utilize computational resources from ICDS to explore what kind of properties a material will have, from a quantum perspective, that may be particularly good for identifying dark matter,” Blanco said. “I want to use AI models to investigate the properties of materials that would be effective for detectors and to make the scattering processes more efficient.”

ICDS resources, specifically the graphics processing units (GPUs) will allow Blanco to run models on very large datasets on a much faster timescale.

In the future, these materials — such as stilbene, an organic molecular crystal — could be used to then create detectors needed to catch direct signatures or interactions of new particles that could constitute dark matter.

Other ways to observe the effects of dark matter include looking at how the stars behave in galaxies and how galaxies move in respect to one another, according to Blanco.

“If we close our eyes and forget that the Lambda-CDM model exists, we find that we can’t make stars or galaxies move in the way that they do without a dark component that doesn’t interact strongly with anything else. We can look at how stars in galaxies rotate. Without dark matter, stars would be rotating far too fast around the center of the galaxy to still be bound to that particular galaxy. The only thing holding the galaxies and stars together would be if there was more mass than what we observe, which would be the dark matter.”

This is also an indirect way of weighing dark matter, Blanco said.

His research opens up opportunities for various interdisciplinary collaborations within Penn State and beyond.

“It’s not just that Penn State has this wonderful set of computational facilities at ICDS, but Penn State is a hub that bridges the gaps between theorists and experimentalists who are a part of a world class set of resources across different institutes, departments and campuses,” Blanco said.

Blanco aims to create collaborations within the ICDS community, as well as build upon the broader larger particle dark matter community within the Department of Physics.

“A key part of my research program is to have a group that can do table-top experiments, theory, and computational analysis and serve as a communicator between these fields,” he said.

Share

Related Posts

- Professor receives NSF grant to model cell disorder in heart

- Featured Researcher: Nick Tusay

- Multi-institutional team to use AI to evaluate social, behavioral science claims

- NSF invests in cyberinfrastructure institute to harness cosmic data

- Center for Immersive Experiences set to debut, serving researchers and students

- Distant Suns, Distant Worlds

- CyberScience Seminar: Researcher to discuss how AI can help people avoid adverse drug interactions

- AI could offer warnings about serious side effects of drug-drug interactions

- Taking RTKI drugs during radiotherapy may not aid survival, worsens side effects

- Cost-effective cloud research computing options now available for researchers

- Costs of natural disasters are increasing at the high end

- Model helps choose wind farm locations, predicts output

- Virus may jump species through ‘rock-and-roll’ motion with receptors

- Researchers seek to revolutionize catalyst design with machine learning

- Resilient Resumes team places third in Nittany AI Challenge

- ‘AI in Action’: Machine learning may help scientists explore deep sleep

- Clickbait Secrets Exposed! Humans and AI team up to improve clickbait detection

- Focusing computational power for more accurate, efficient weather forecasts

- How many Earth-like planets are around sun-like stars?

- SMH! Brains trained on e-devices may struggle to understand scientific info

- Whole genome sequencing may help officials get a handle on disease outbreaks

- New tool could reduce security analysts’ workloads by automating data triage

- Careful analysis of volcano’s plumbing system may give tips on pending eruptions

- Reducing farm greenhouse gas emissions may plant the seed for a cooler planet

- Using artificial intelligence to detect discrimination

- Four ways scholars say we can cut the chances of nasty satellite data surprises

- Game theory shows why stigmatization may not make sense in modern society

- Older adults can serve communities as engines of everyday innovation

- Pig-Pen effect: Mixing skin oil and ozone can produce a personal pollution cloud

- Researchers find genes that could help create more resilient chickens

- Despite dire predictions, levels of social support remain steady in the U.S.

- For many, friends and family, not doctors, serve as a gateway to opioid misuse

- New algorithm may help people store more pictures, share videos faster

- Head named for Ken and Mary Alice Lindquist Department of Nuclear Engineering

- Scientific evidence boosts action for activists, decreases action for scientists

- People explore options, then selectively represent good options to make difficult decisions

- Map reveals that lynching extended far beyond the deep South

- Gravitational forces in protoplanetary disks push super-Earths close to stars

- Supercomputer cluster donation helps turn high school class into climate science research lab

- Believing machines can out-do people may fuel acceptance of self-driving cars

- People more likely to trust machines than humans with their private info

- IBM donates system to Penn State to advance AI research

- ICS Seed Grants to power projects that use AI, machine learning for common good

- Penn State Berks team advances to MVP Phase of Nittany AI Challenge

- Creepy computers or people partners? Working to make AI that enhances humanity

- Sky is clearing for using AI to probe weather variability

- ‘AI will see you now’: Panel to discuss the AI revolution in health and medicine

- Privacy law scholars must address potential for nasty satellite data surprises

- Researchers take aim at hackers trying to attack high-value AI models

- Girls, economically disadvantaged less likely to get parental urging to study computers

- Seed grants awarded to projects using Twitter data

- Researchers find features that shape mechanical force during protein synthesis

- A peek at living room decor suggests how decorations vary around the world

- Interactive websites may cause antismoking messages to backfire

- Changing how government assesses risk may ease fallout from extreme financial events

- ICS co-sponsors Health, Environment Seed Grant Program

- Penn State’s Leadership in AI Research

- Seven ICS faculty receive promotions