Are egg cells in aging primates protected from mutations?

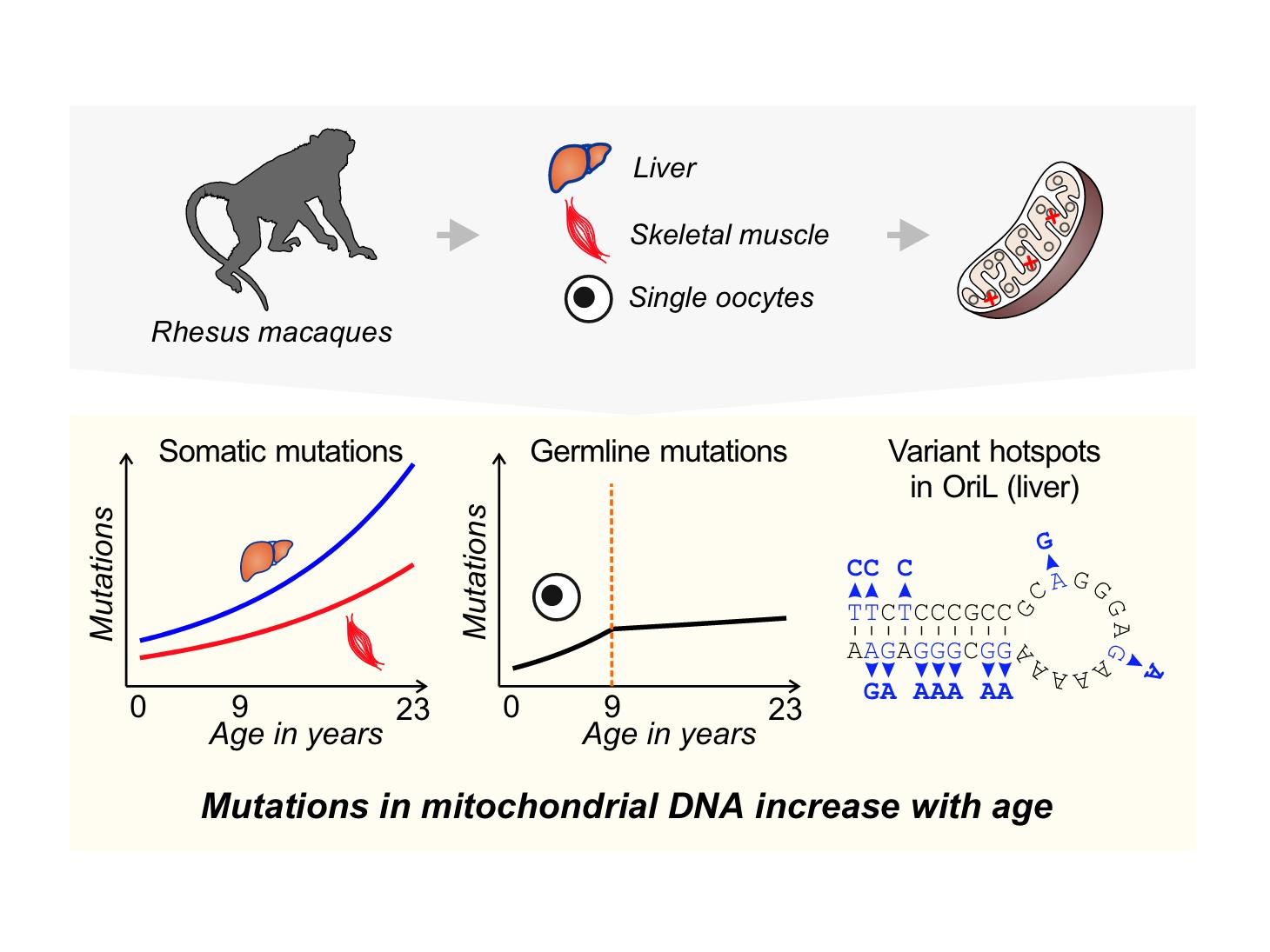

Posted on April 5, 2022A new study shows that mutation frequencies in mitochondrial DNA are lower, and increase less with age, in the precursors of egg cells than in the cells of other tissues in a primate

Story originally published on Penn State News

UNIVERSITY PARK, Pa. — New mutations occur at increasing rates in the mitochondrial genomes of developing egg cells in aging rhesus monkeys, but the increases appear to plateau at a certain age and are not as large as those seen in non-reproductive cells, like muscle and liver. A new study using extremely accurate DNA sequencing methodology suggests that there may be a protective mechanism that keeps the mutation rate in reproductive cells relatively lower compared to other tissues in primates, a fact that could be related to the primate — and therefore human — propensity to reproduce at later ages.

“Because of the diseases in humans caused by mutations in the mitochondrial genome and the trend in modern human societies to have children at older ages, it’s vital to understand how mutations accumulate with age,” said Kateryna Makova, Verne M. Willaman Chair of Life Sciences at Penn State, ICDS associate, and a leader of the research team “My lab has been interested in studying mutations — including mutations in mitochondrial DNA — for a long time. We are also interested in evolution, so we wanted to see how mutations in mitochondrial DNA accumulate in reproductive cells because these mutations can be passed down to the next generation.”

A paper describing the study, led by researchers at Penn State, appears online the week of April 4, 2022, in The Proceedings of the National Academy of Science.

Mitochondria are cellular organelles — often called the powerhouse of the cell because of their role in energy production — that have a genome of their own separate from the cell’s “nuclear genome,” which is located in the nucleus and is what we often think of as “the” genome. Mutations in mitochondrial DNA contribute to multiple human diseases but studying new mutations is challenging because true mutations are difficult to distinguish from sequencing errors, which occur at a higher rate than mutation rates in most sequencing technologies.

“To overcome this difficulty, we used a method called ‘duplex sequencing,’” said Barbara Arbeithuber, a postdoctoral researcher at Penn State at the time of the research who is now a research group leader at Johannes Kepler University Linz in Austria. “DNA is composed of two complementary strands, but most sequencing techniques only look at the sequences from one of the strands at a time. In duplex sequencing, we build consensus sequences for each strand individually and then compare the two. Errors are extremely unlikely to happen at the same place on both strands, so when we see change on both strands, we can be confident that it represents a true mutation.”

The team sequenced the mitochondrial genome from muscle cells, liver cells, and oocytes — precursor cells in the ovary that can become egg cells — in rhesus macaques that ranged in age from one to 23 years. This age range covers almost the entire reproductive lifespan of the monkeys. Tissues for the study were collected opportunistically over the course of several years from primate research centers when animals died of natural causes or were sacrificed because of diseases not related to reproduction. Oocytes, and not sperm cells, were used because mitochondria are inherited exclusively through the maternal line.

Overall, the researchers saw an increase in the mutation frequency in all of the tested tissues as the macaques aged. Liver cells experienced the most dramatic change with a 3.5-fold increase in mutation frequency over approximately 20 years. The mutation frequency in muscle increased 2.8-fold over the same time span. The mutation frequency in oocytes increased by 2.5-fold up to age nine, at which point it remained steady.

“From a reproductive biology perspective, oocytes are really interesting and special cells,” said Francisco Diaz, associate professor of reproductive biology at Penn State. “They are generated prior to birth and sit in the ovary for years and years and years, and then a few of them are activated each reproductive cycle. So, you would expect them to accumulate a lot of mutations over that time, but instead we see that they accumulate mutations for a while and then they do not. This seems to indicate that the germ line — reproductive cells like egg and sperm — may be more resilient than we thought.”

In addition to changes in the rate of mutations over time, the research team also identified variation in mutation frequency across the mitochondrial genome, including several hotspots where mutations occurred much more frequently than you would expect by chance that varied by tissue. One of the hotspots was located in the region responsible for copying of mitochondrial genomes.

“Although it is very challenging to perform a study like this in humans, using a primate model species gives us a close approximation,” said Makova. “Our results suggest that primate oocytes might have a mechanism to protect or repair their mitochondrial DNA, an adaptation that helps to allow later reproduction. The precise mechanism leading to the plateau in mutation frequency in oocytes remains enigmatic, but it might act at the level of elimination of defective mitochondria or oocytes.”

In addition to Makova, Arbeithuber, and Diaz, the research team includes James Hester, Alison Barrett, Bonnie Higgins, Kate Anthony, and Francesca Chiaromonte at Penn State, and Marzia Cremona, a former postdoctoral researcher at Penn State who is now assistant professor at Université Laval in Québec, Canada. The research was funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health and a Schrödinger Fellowship from the Austrian Science Fund. Additional funding was provided by the Office of Science Engagement in the Penn State Eberly College of Sciences, and the Huck Institute of the Life Sciences and the Institute for Computational and Data Sciences at Penn State.

Share

Related Posts

- Professor receives NSF grant to model cell disorder in heart

- Featured Researcher: Nick Tusay

- Multi-institutional team to use AI to evaluate social, behavioral science claims

- NSF invests in cyberinfrastructure institute to harness cosmic data

- Center for Immersive Experiences set to debut, serving researchers and students

- Distant Suns, Distant Worlds

- CyberScience Seminar: Researcher to discuss how AI can help people avoid adverse drug interactions

- AI could offer warnings about serious side effects of drug-drug interactions

- Taking RTKI drugs during radiotherapy may not aid survival, worsens side effects

- Cost-effective cloud research computing options now available for researchers

- Costs of natural disasters are increasing at the high end

- Model helps choose wind farm locations, predicts output

- Virus may jump species through ‘rock-and-roll’ motion with receptors

- Researchers seek to revolutionize catalyst design with machine learning

- Resilient Resumes team places third in Nittany AI Challenge

- ‘AI in Action’: Machine learning may help scientists explore deep sleep

- Clickbait Secrets Exposed! Humans and AI team up to improve clickbait detection

- Focusing computational power for more accurate, efficient weather forecasts

- How many Earth-like planets are around sun-like stars?

- SMH! Brains trained on e-devices may struggle to understand scientific info

- Whole genome sequencing may help officials get a handle on disease outbreaks

- New tool could reduce security analysts’ workloads by automating data triage

- Careful analysis of volcano’s plumbing system may give tips on pending eruptions

- Reducing farm greenhouse gas emissions may plant the seed for a cooler planet

- Using artificial intelligence to detect discrimination

- Four ways scholars say we can cut the chances of nasty satellite data surprises

- Game theory shows why stigmatization may not make sense in modern society

- Older adults can serve communities as engines of everyday innovation

- Pig-Pen effect: Mixing skin oil and ozone can produce a personal pollution cloud

- Researchers find genes that could help create more resilient chickens

- Despite dire predictions, levels of social support remain steady in the U.S.

- For many, friends and family, not doctors, serve as a gateway to opioid misuse

- New algorithm may help people store more pictures, share videos faster

- Head named for Ken and Mary Alice Lindquist Department of Nuclear Engineering

- Scientific evidence boosts action for activists, decreases action for scientists

- People explore options, then selectively represent good options to make difficult decisions

- Map reveals that lynching extended far beyond the deep South

- Gravitational forces in protoplanetary disks push super-Earths close to stars

- Supercomputer cluster donation helps turn high school class into climate science research lab

- Believing machines can out-do people may fuel acceptance of self-driving cars

- People more likely to trust machines than humans with their private info

- IBM donates system to Penn State to advance AI research

- ICS Seed Grants to power projects that use AI, machine learning for common good

- Penn State Berks team advances to MVP Phase of Nittany AI Challenge

- Creepy computers or people partners? Working to make AI that enhances humanity

- Sky is clearing for using AI to probe weather variability

- ‘AI will see you now’: Panel to discuss the AI revolution in health and medicine

- Privacy law scholars must address potential for nasty satellite data surprises

- Researchers take aim at hackers trying to attack high-value AI models

- Girls, economically disadvantaged less likely to get parental urging to study computers

- Seed grants awarded to projects using Twitter data

- Researchers find features that shape mechanical force during protein synthesis

- A peek at living room decor suggests how decorations vary around the world

- Interactive websites may cause antismoking messages to backfire

- Changing how government assesses risk may ease fallout from extreme financial events

- Penn State’s Leadership in AI Research

- ICS co-sponsors Health, Environment Seed Grant Program

- Symposium at U.S. Capitol seeks solutions to election security